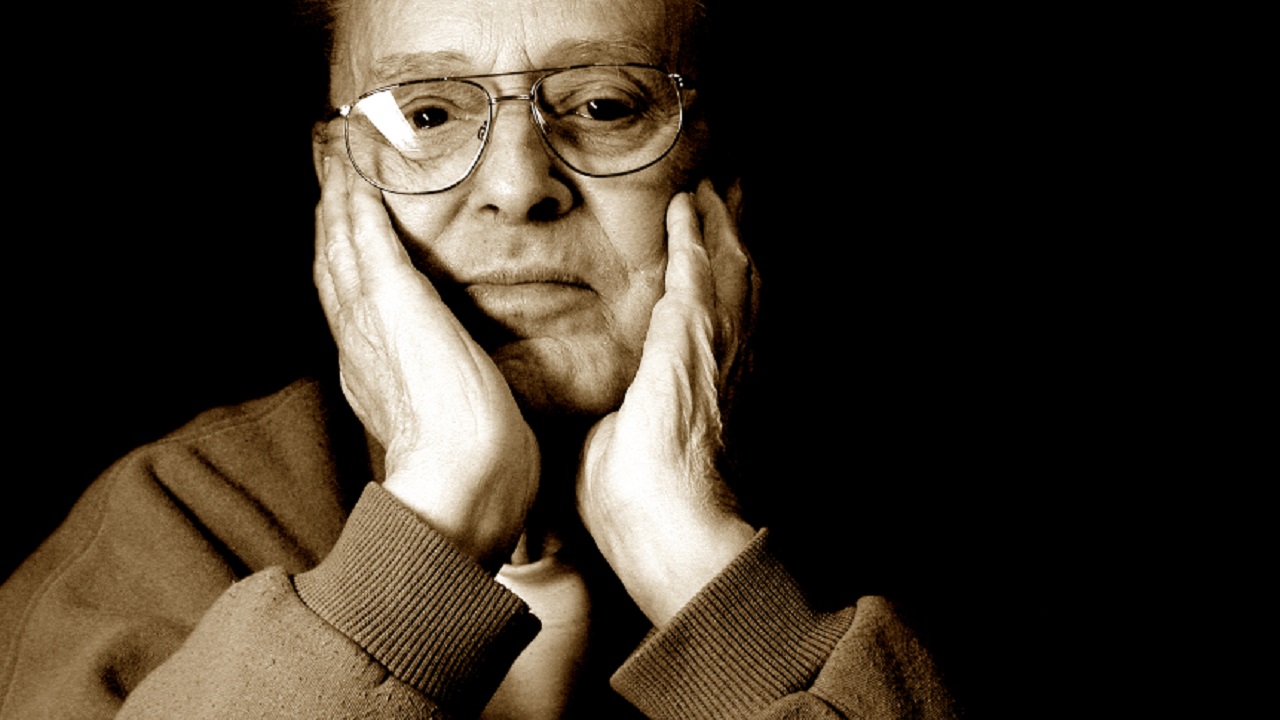

Years ago, I was looking online for caregiver support groups for people caring for diagnosed schizophrenics when I found an article that explained a lot about my father-in-law, Rodger.

I felt very alone when caring for him. And, I must admit, I believed our situation was special. It was more complicated than a case of Alzheimer’s disease or some other type of dementia. (As if these conditions are anything less than devastating to our loved ones or us.)

I hope those of you reading this will forgive me for the arrogance of my assumptions at that time. It was born of ignorance, fatigue and the overwhelming hope that most people are not as severely stricken as Rodger was.

Unfortunately, the more I learn from my fellow caregivers, the more I understand the depth and breadth of suffering from these terrible diseases and how many are dealing with them now.

The Undeniable Link Between Physical and Mental Health

The opening line of the article I found all those years ago reads: “Older adults who have schizophrenia appear to face a higher risk of getting dementia, new research suggests.”

In the study this article covers, researchers discovered that the rate of dementia in elderly patients with schizophrenia is twice that of older non-schizophrenic patients. Rodger was among that group.

They also found that patients with schizophrenia have higher rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure and hypothyroidism.

Rodger had COPD, congestive heart failure and took medication for his malfunctioning thyroid. He also had Parkinson’s disease, which often leads to dementia and difficulty swallowing (a condition called dysphagia). All Rodger’s food had to be pureed and all his liquids had to be thickened to the consistency of honey. He was always at risk of accidentally inhaling food particles or saliva into his lungs and developing aspiration pneumonia. This happened several times and each episode weakened him more.

It’s no surprise that his body eventually gave out. The miracle is that he lived as long as he did.

The lead researcher of the study, Hugh Hendrie, M.B., Ch.B., D.Sc., professor emeritus of psychiatry at Indiana University School of Medicine, distinguished scientist at Regenstrief Institute, and center scientist at the IU Center for Aging Research, said, “The good news is those with schizophrenia are living longer; the bad news is they are getting more of the serious physical illnesses than other people.”

Hendrie and his team weren’t surprised by their findings that health care use was higher in those with schizophrenia, but they did not anticipate that their hospital admissions were almost always for physical illnesses instead of their mental health condition.

“What is needed is a health care system that integrates the mental health and physical health services needed by someone with schizophrenia,” Hendrie emphasized.

I heartily agree. This study may not seem all that notable, but it is research like this that identifies and spreads awareness of the weak points in our health care system so we can make improvements. I experienced my fair share of these firsthand while caring for my father-in-law. I’m still baffled by how the medical professionals who treated him were laser-focused on either his physical health or his mental health. It seemed that nobody could evaluate him as a whole patient, taking into account both his somatic and psychological symptoms. His health suffered because of this. One instance in particular stands out in my mind.

After a devastating psychotic break, Rodger was discharged from the psychiatric ward with a severe case of pneumonia. He ended up in the ICU two days later.

While he was on the medical ward being treated for pneumonia, the nurses were apparently unaware of his psychiatric history. He hid his antipsychotic medication in his cheek and spit it out when hospital personnel left the room.

It wasn’t until I recognized his symptoms were worsening and insisted on a meeting with all his doctors and a patient advocate that both his mental and physical conditions were brought under control again. If left unrecognized and untreated, either illness could have led to his death much earlier than it occurred.

Knowledge Is Power

Perhaps if Rodger’s care team had known the information in this study, his doctors and nurses could have been watching for symptoms of these complications and made me, his caregiver, aware of them as well.

While it wouldn’t have changed the eventual outcome, having this information might have reduced the guilt and anxiety I felt each time Rodger developed another ailment. With every new diagnosis, I questioned my value as a caregiver and a daughter-in-law.

What was I doing wrong? What more could I do to protect him? What was I missing that could help him avoid another setback? Would I not have had migraine headaches and panic attacks if I had known that the insidious decline in his health had nothing to do with the quality of care he received at home?

I’ll never know.

I can’t help but wonder how many doctors treating elderly patients with schizophrenia are aware of this information and how many are sharing it with their patients’ caregivers, sparing them from being in the position to say, “I wish I had known.”

Discovering associations between seemingly unrelated health conditions, staying up to date on medical research, using this information in everyday applications and sharing it with others is critical. I urge all family caregivers to use reliable sources to learn as much as they can about all their loved ones’ health conditions and seek out doctors who provide integrated, whole-person care to their patients.

Elders with both physical and mental illnesses are incredibly vulnerable. If your loved one has a history of schizophrenia or another behavioral health condition, I hope this information helps you understand a bit more about what is happening and helps you prepare for what you both may face in the future. I’d hate to think of anyone else having to say, “I wish I had known.”